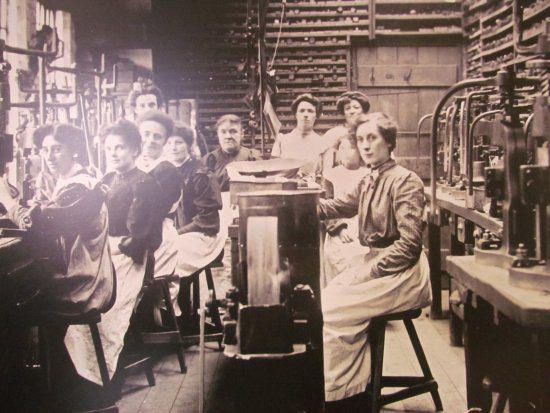

The 19th century was a period of industrial growth in Birmingham. The city was considered the industrial heart of the nation, with a vast range of manufacturing industries. Most heavy industry was concentrated here, but rather than large factories, Birmingham’s industry was dominated by small workshops. Working conditions were harsh, especially for women and children. Read more on birminghamka.

Factory Acts

Birmingham was known as the “City of a Thousand Trades.” Its small workshops specialised in a vast range of industries, and women worked everywhere—laundries, clothing workshops, kitchens, slaughterhouses, foundries, chocolate factories, and even mines.

One of the main problems at the time was the lack of regulated working hours. There were no official limits on working time. In 1844, the first Factory Act reduced working hours for women. Until then, they worked the same hours as men—or even longer. However, there was a flaw in the law: it only applied to textile mills, where most female workers were employed.

This created a problem. The vast majority of workplaces in Birmingham were workshops that operated illegally and were therefore outside the scope of labour laws. People desperate for money took jobs wherever they could, without concern for the employer’s legal status. Birmingham was a centre of heavy industry—metalworking, jewellery making, and food production. The famous Cadbury chocolate factory was located on Bull Street.

Textile mills were rare in the city. It was only in 1867 that the law was extended to workshops. From then on, the maximum working day for women was set at 10.5 hours.

The Downside

Lord Ashley was a well-known activist who campaigned to reduce working hours for women and children to ten hours per day. However, this had unintended consequences. Employers began paying lower wages, forcing women to work overtime simply to make ends meet, as the government did not regulate salaries.

Lord Ashley saw hard labour as a threat to society. He directly linked physical toil to infertility, and he was right—poor working conditions led to miscarriages and maternal exhaustion. Even women who already had children found it nearly impossible to fulfil their maternal duties due to lack of time and energy. As a result, the number of homeless children increased.

Ashley’s perspective was shaped by Victorian ideals of women as delicate and refined beings who had never lifted anything heavier than a book. However, working-class women did not fit this ideal. In Birmingham, life was particularly tough for women compared to other cities.

Despite Lord Ashley’s efforts, his proposals met strong opposition. Many MPs viewed his initiatives as harmful. Birmingham’s heavy industry was export-driven, and reducing working hours meant lower production and financial losses.

There were also concerns that such laws would reduce the working class’s motivation. Many MPs were factory owners themselves and did not want to lose profits. The London government also opposed these reforms—19th-century Britain was competing with Europe, and any reduction in production was seen as unacceptable.

Health and Safety Law

While reducing working hours was difficult, enforcing workplace safety regulations was somewhat easier. For example, factories began to be treated with limewash to prevent disease, and large machines were fenced off for worker protection. Rules on the maintenance and repair of machinery were introduced.

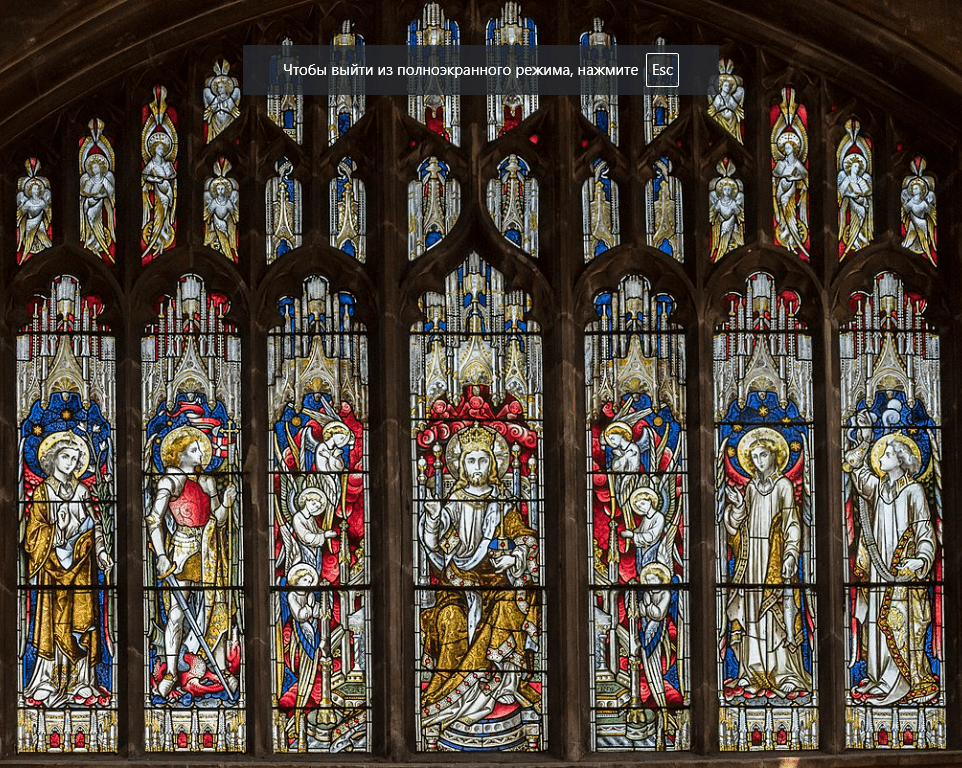

This legislation, known as the 1844 Factory Act, was Birmingham’s first official law on workplace safety and health. It was crucial, given the number of hazardous industries in the city, such as the stained-glass factory Hardman & Co..

Working hours for women fluctuated with changes in government. Each new ruling party introduced new laws. Meanwhile, children worked alongside women in Birmingham’s factories and workshops. Initially, labour laws for children mirrored those for women.

Before 1864, the Factory Acts contained no ventilation regulations for workplaces—despite their necessity in industries involving chemicals, such as jewellery workshops. Poor ventilation led to illness and death, particularly among child workers. The 1878 Factory Act established a maximum working week of 56 hours for women and children.

What Were the Alternatives?

Despite Birmingham’s hundreds of factories and workshops, there were few light industry jobs for women. Unlike cities with large textile industries, Birmingham lacked large-scale garment factories. This issue extended beyond Birmingham—the West Midlands was historically dominated by mines, and women often had to work in them. They wore a special uniform—shirts and trousers (tight at the ankles and wide at the waist). While they were not directly involved in mining, they worked on processing materials, often in exhausting conditions.

The same was true for children. Orphans and homeless children were sent to workhouses, which decided their fates. Some were sent to factories, others to farms, and some were even trafficked into brothels.

Prostitution was a significant issue in Birmingham’s history. Laws were introduced to regulate the sex trade, and social organisations attempted to combat brothels, but these efforts had little success. Eradicating prostitution was difficult, especially when those enforcing the laws were middle-class officials disconnected from the realities of working-class life.

Middle- and upper-class women were oblivious to the hardships faced by working-class women, who had no real choices—only hard labour in factories and mines, or prostitution.

Modern Equality

In 1989, all previous Factory Acts were repealed, as they were deemed discriminatory. New laws and societal changes recognised that women should have the right to decide their own working hours. By the late 20th century, working conditions were incomparable to the brutal labour of the 19th century. The 1961 Factory Act placed greater responsibilities on employers to protect worker safety.

When the UK joined the European Union, employment regulations became aligned with EU Working Time Directives.

Early labour laws in Birmingham aimed to protect women from premature death, but they also sought to fit them into the Victorian ideal of womanhood. However, no legislator ever asked working-class women what they actually needed.

Birmingham’s 19th-century labour laws mirrored broader trends—women were expected to conform to middle- and upper-class ideals, rather than having their real needs and desires considered. This led to employers avoiding hiring women, forcing them to fight for the right to financially support their families.